Figure 1: Front of parcel card from Preschen (the back is completely blank).

by Roger Morrell

Most readers will be broadly familiar with the Austro-Hungarian process of sending a parcel through the post. The Post Office clerk issues a Postbegleitadresse (declaration) card which contains the details of the sender, the addressee, the weight and the postage fee, and affixes the stamps to pay that fee. Each parcel is given a uniquely numbered paper sticker which is glued to the top of the card, and a larger version is stuck on the parcel, thus relating the card to the parcel. The larger part of the card and the parcel are sent together to the destination. On arrival at the destination post office, the card is delivered to the addressee, who then has to make arrangements to collect the parcel from the post office (there was no home delivery), signing the back of the Postbegleitadresse card. The small fee that was paid is receipted on the back of the card using postage due stamps (in Austria only, not Hungary!). The vast majority of parcel cards that are available to collectors show that this process was fairly straightforward and worked most of the time. Extra services included insurance and cash-on-delivery.

However, the system was not fool-proof. Should the parcel card go missing en route, this was usually corrected at the destination post office which issued an Ersatz-Post-Begleitadresse (substitute declaration) card, and sent this to the intended recipient in the normal way. But what happens when a parcel goes missing or its contents are tampered with? Presumably the card arrives at the destination office, but cannot be married up with a parcel. The intended recipient would be notified in the usual way, but then the bureaucracy kicks in. The following three examples from the WWI period provide some evidence.

| Back to Austrian Stamps homepage |

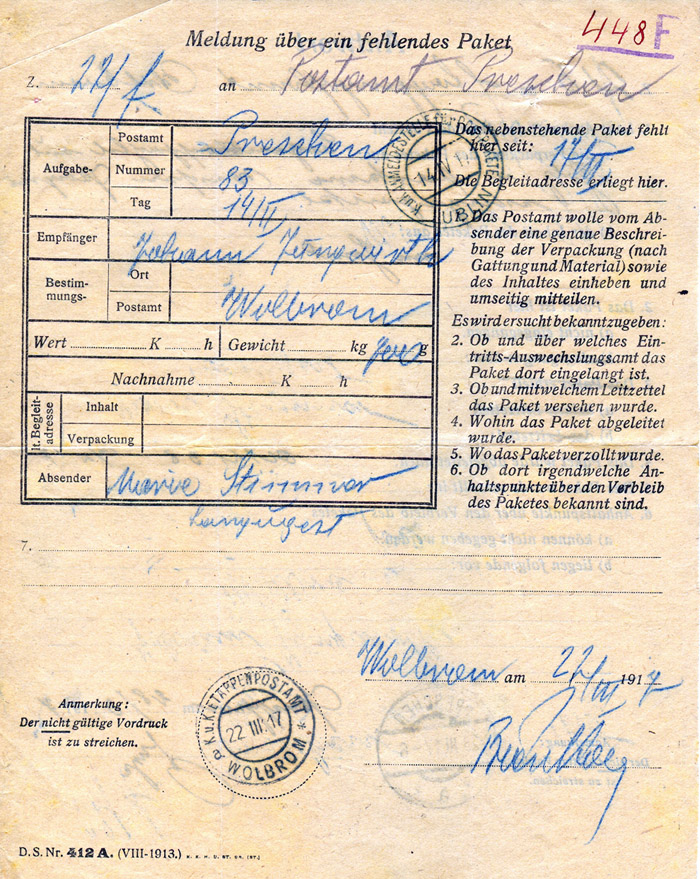

Figure 1: Front of parcel card from Preschen (the back is completely blank).

Figure 1 shows a usual type of parcel card employed for transmission of a parcel of Wäsche (washing) weighing 700 g, charged 60h carriage and sent on 14 February 1917 by one Marie Stimmer Lungugest (?: difficult to decipher – we shall call her just Marie) from Preschen in Bohemia to a Johann Jungwirth based with the k.k. Gendarmerie at Wierzchowisko, Etappenpostamt Wolbrom (which is about 60 km north of Krakau) in Russian Poland. The card arrived in Wolbrom on 17 February, but it appears the parcel did not. The back of the card has no markings whatsoever to indicate that it was collected. Separate communication between Marie and Johann must have occurred, because on 22 March Johann initiated an enquiry. Form DS Nr 412A (VIII-1913), Meldung über ein fehlendes Paket, was completed at Wolbrom Etappenpostamt for a 700g missing packet (Figure 2), which was sent back to Preschen. On the back, the enquiry Antwort (answer), was dealt with at Preschen on 28 March, which in scrawly gothic handwriting basically described the nature of the packing and confirmed that the packet containing one shirt was duly sent on 14 February. This was addressed back to Wolbrom. The next step appears to have been that the ‘case’ was sent to the Anmeldestelle für Postpakete (notification office for postal packets) in Lublin (datestamp at the top) where it arrived on 14 April.

Figure 2: Front of the Meldung document filled out by the intended recipient of the shirt.

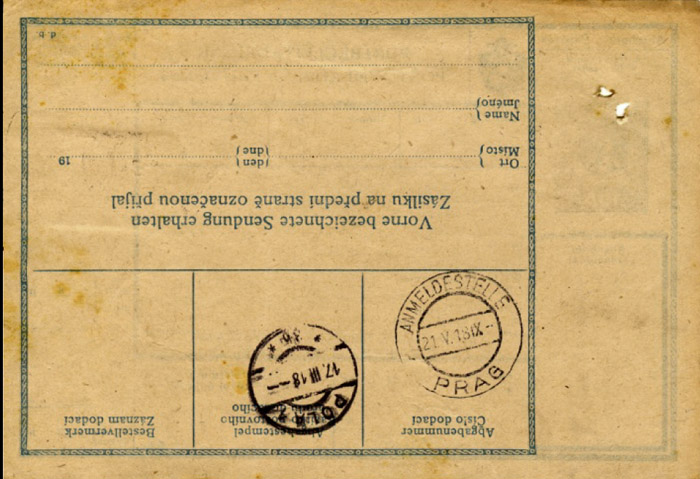

Figure 3: Reverse of the Meldung document.

On or about this date, this office in Lublin issued a second Meldung document (Figure 4) addressed to the k.k.Postamt Szczakowa Zoll (about 80 km northwest of Krakau – seems to be a big railway junction), which must have been a sufficiently common occurrence because this has been done using a rubber cachet. The handwritten response on the reverse of this form (Figure 5), addressed back to Lublin, again using a rubber cachet, says: Das Pkt bis 20/II nicht nachweisbar. Im Zugangsfalle nach 20/II nach Wolbrom zollfrei abgefertigt / die zollfreie Pkte nach Polen sind vom 20/II nicht mehr konsigniert. Translated this says: ‘The parcel was not traceable up to 20 February. In any event after 20 February it would have free from customs clearance. Customs clearance free parcels to Poland are no longer consigned from 20/II.’ In other words, ‘it didn’t come to us for customs clearance before 20 February, and now we don’t do parcels destined for Poland anyway – nothing to do with us, guv’. The datestamp at the bottom is of Szczakowa ‘5b’ on 19.V.17. This document was received back in Lublin on 20 May.

Figure 4: Second Meldung document, front side

Figure 5: Second Meldung document, reverse side/

Next, the Lublin office filled out an Erklärung des Empfängers (declaration of recipient, Figure 6) form Nr 3712/16, printed by the book press of the M-G-G, Lublin (Militär Grenz Gebiet?) and sent it to the Wolbrom office where our intended recipient signed on 26 May to say that ‘neither through the post nor by another means has he received his shirt’. What happened next is anyone’s guess, but this bundle of papers was pinned together and probably archived back in Lublin, or even Vienna. The existence of this specially printed form suggests there was an awful lot of missing parcels!

Figure 6: Erklärung document

This set of documents raises some questions:

1. Before 20 February 1917 were all incoming parcels to newly occupied Russian Poland subject to routing through Szczakowa for customs inspection?

2. Lublin is a long way ENE of Krakau – it seems odd that the office sorting out problems with parcels would be so far out of the way. Was Lublin a big sorting centre for troops on the Eastern Front after the Russian expulsion from Galicia in 1915?

This concerns a rather interesting Feldpostbegleitadresse (field-post declaration form) (Figure 7) sent from Odessa at the end of September 1918, part of the abortive final foray up the Volga river for the Austrian army and the Danube Flotilla. The sender is Linienschiffskapitän Mallinarich of the Hafenkommando, Odessa, Ukraine, who is sending a Kistchen (little crate) of Lebensmittel (food) to his wife in Königliche Weinberge, Bohemia. The 5 kg weight is charged 50h + 1k = 1.50k, and because there are no stamps available, a large ‘G.B.’ cachet has been applied, which probably means Gebühr Bezahlt (fee paid). The partly visible two-line cachet across the top edge of the card reads K.u.k. Heimpaketabschubstelle Odessa / Feldpost (despatch office for parcels destined for the homeland). The card is stamped with an FPA 240b datestamp 30.IX.18.

Figure 7: Front of parcel card sending 5 kg of food from Odessa to Königliche Weinberge

Figure 8: Reverse of the parcel card with the manuscript annotations.

The reverse of the card (Figure 8) reveals that the parcel did actually arrive quite quickly in Königliche Weinberge, on 6 October, but it looks like the recipient, Marie Basch, thought something was wrong. At the right-hand side the manuscript reads ‘Richtige Gewicht 2 kg 000 gr avisiert 19.X.18’ (correct weight 2.0 kg advised) and signed. In the lower part of the card where the recipient would normally sign for receipt, Marie Basch has commented ‘gegen Vorbehalt des Schadensersatzes’ (with the proviso of the damage). So this implies that the crate was damaged, probably partly prised open, and some of the contents pilfered. There is no postage due stamp on the reverse, so presumably the recipient’s charge was waived. There are rusty pinholes visible in the card, which means that another document was probably attached to it when the paperwork was sent, probably to Prag, for investigation. Unfortunately that did not come with the card, but it looks as though a formal complaint was made.

This one is about a crate of pečivo/Gebäck (a collective noun in both Czech and German languages meaning breads, pastries, cakes, etc.) that went missing between Peček an der Staatbahn / Pečkyna Státní Oráze and the Naval Base in Pola down on the Adriatic coast. The original bilingual German/Bohemian parcel card (Figure 9) was made out on 13 March 1918 to send a crate of pečivo weighing 5kg to a family member on the cruiser S.M.S. ‘Zrinyi’ at the usual mailing address of Marinefeldpostamt Pola. The postal charge was 80h, and the card duly arrived in Pola on 17 March as evidenced by the datestamp on the reverse. However, it seems that the crate was not signed for.

Fig 9: Parcel card sending 5kg of pastries to Pola

Figure 9: reverse of card - arrival in Pola on 17 March.

There must have been some communication between the sender and the intended recipient, because on 22 April in Peček/ Pečky, the sender filed a Nachfrageschreiben, a foolscap-sized enquiry document (type D.S. Nr. 438, X/1912, Figure 10), asking for the parcel to be traced, for which the sender had to pay 25h in stamps. (Seems a bit pointless, because the value of the crate was not declared and hence the parcel was not insured, and because by this time nothing inside the crate would have been edible, at least by modern standards!) On 27 April, this second document reached the K.u.k. Marinefeldpostamt Pola, where the clerk indicated in the top right-hand box (by strike-out and underlining), that Die Sendung... ist nicht eingelangt, i.e. the sending was not received.

Figure 10: Nachfrageschreiben to trace the sending.

text on the reverse of fig 10.

A third document then appears to have been attached (the staple holes in all three documents match up). This is a double-sided flimsy sheet that we saw in Case 1, of type D.S. 412A (VIII/1913) entitled Meldung über ein fehlendes Paket (notification of a missing packet), Figures 11 and 12. The intended recipient was clearly having his two penn’orth as well. He filled in this form about the missing crate at the Pola 1 civilian post office, where it received the barred octagonal straight-line datestamp of 29 April.

Figure 11: Meldung document completed by intended recipient, front side.

Figure 12: Meldung document, reverse side.

All three documents then passed to the K.K. Fahrpost-abteilung Pola, perhaps actually meeting up there, where a second clerk wrote ‘fehlend gemeldet am 30/IV 18’, i.e. ‘missing in registering the arrival’ (of the sending) on the middle right-hand box on the Nachfrageschreiben, and then applied his big oval cachet. The package of documents was folded up and sent to Peček / Pečky, probably inside an official envelope. On the 6 May, someone wrote on the back of the Nachfrageschreiben in Bohemian: vyrozumĕní (notification) and dated it 6/V 918 (see Fig 10 reverse). Presumably at this point the sender was informed that the crate was untraceable. Beneath this is written in the same hand: ‘Die Meldung am 7/V 918 eingelangt’ (the notification received on 7 May). The postal clerk then datestamped the back of the flimsy Meldung document on 8 May, and also stamped it with the long single-line cachet ‘Ausgleich nicht gefunden’ (‘sending not found’, Figure 12), probably to indicate that it wasn’t still sitting somewhere in Peček/Pečky. The contents also seem to have been changed from 5kg of pečivo to somewhat less palatable 4.25 kg of Schmalz (lard)!

Now the package of documents had to go back to the intended recipient, presumably to inform him that the crate was untraceable. The back of the flimsy Meldung document has an Anmeldestelle Triest datestamp of 16 May, but not one of Pola, so perhaps the post office knew that the ship had moved on from Pola. Finally, the package of documents was sent to Prag/Praha, probably a central archive. On 20 May, the lowest box on the right-hand side of the Nachfrageschreiben was completed by yet another clerk who wrote ‘Unter den Feldpostpaketen nicht nachweisbar’ (not traceable amongst the field-post packets). He then applied the bilingual cachet K.k. Paketanmeldestelle in Prag / C.k. ohlašovna banku v Praze, and dated it 20/5 18. Finally, the back of the original parcel card and the front of the flimsy Meldung document are both datestamped Anmeldestelle Prag on 21.V.18.

This little package (the documents, not the pečivo!) presumably sat in the Prag archive until ‘liberated’. It makes a nice, if a tad complicated, postal history tale, but also links well with real history. In 1918, food was becoming scarce in many parts of the Empire, especially in the cities. Naval rations were not up to much either, so maybe the family thought they would be doing their sailor son a favour by sending him some food. The awkward step in those times, of course, was to have to declare on the parcel card that there was something tasty inside - remembering also that only limited items could be sent to the military and failure to correctly describe the contents led to confiscation! This must have made it easy pickings for one of the less scrupulous employees of the post office or the railway system. It was probably quite easy to leave a ‘target’ crate behind en route (or to break into it as in Case 2)! Goodbye pečivo.

Nachfrageschreiben from the WWI period regularly appear in auctions, and are commonly related to missing/stolen fieldpost packets, but until acquiring these examples, I had not seen the Meldung document before. But I don’t understand why it was necessary to have two different documents, one involving paying a fee and the other not. What dictated which type was used when? Are the Meldung documents solely for use by the military?

The author would appreciate any background information or documentation to answer these and other queries dotted throughout the article.

| Back to Austrian Stamps homepage |

©APS. Last updated 30 Dec 2013