| Back to Austrian Stamps homepage |

By A Taylor aided by M Brumby et al

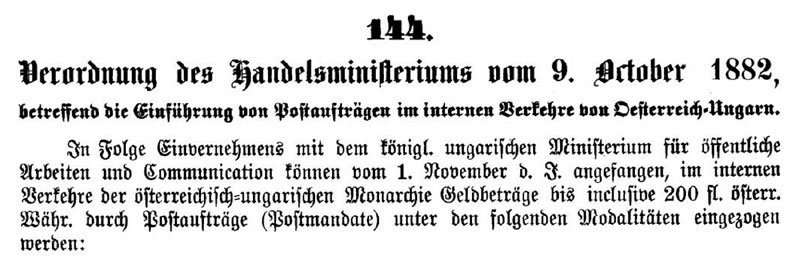

On 1 Nov 1882 the Nachnahmekarte (C.O.D.) service introduced in 1871 was refocussed on the transport of physical goods which were to be paid for on delivery, typically by Nachnahme Postbegleitadresse. A new service was introduced: the Postauftrag (Postal Mandate) service, to handle demands for payment for services that had been or were to be rendered, accompanied by documentation such as invoices. It was announced in a Decree from the Ministry of Trade:

(and so on for 2˝ pages plus a form). As was customary, the text of the Decree was repeated verbatim in a Postverordnung, Nr 84 dated 17 Oct 1882, with the addition that this new system would be publicised in the regional newspapers, and that the existing C.O.D. system remained unchanged. The Postverordnung was accompanied by three pages of Durchführungs-Bestimmungen giving explanatory details for the postal employees, and details of the reverse of the form and of the dual-language versions.

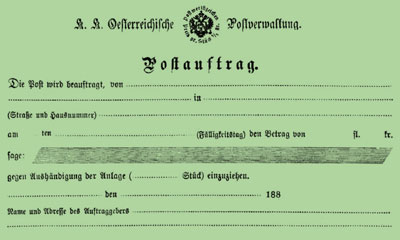

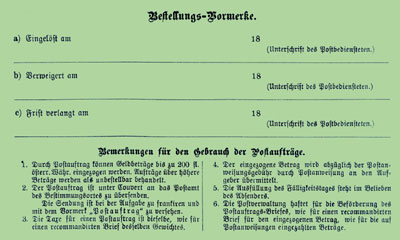

The new service is simplest to explain by an example. Let’s say that Bob wishes Alice to pay him 100 Gulden for something. Bob goes to a Post Office or a Stamp Reseller, buys a Postauftrag form for ˝kr. and fills it in. He puts the form plus his supporting ‘Anlage’ (eg his invoice, bill of exchange, begging letter etc) in an envelope which he supplies; he decides if he wants only one delivery attempt to be made (if yes, he writes "Sofort zurück" on the back of the Postauftrag form); he addresses the envelope to Alice’s Post Office [not to Alice; her details go on the form]; and he takes it to his own. They check the details and enter them in their registers; and sell him adhesives to cover postage plus registration. These are applied to Bob’s envelope which is then transmitted to Alice’s Post Office as a registered letter. There were restrictions:

Alice’s Post Office opens the letter and duly records it. They send the form and the Anlage via the delivery postman to Alice, who reads Bob’s form demanding 100 Gulden and then:

If Alice does pay the 100fl, her Post Office creates a money order (an Auftrags-Postanweisung) in favour of Bob, BUT they deduct the standard charge (for 100fl in 1882, 20kr) from the gross amount of Alice’s cash - so instead of 100 Gulden he would receive 99.80. This Auftrags-Postanweisung is sent through the system to Bob’s Post Office, and eventually Bob’s postman brings him 99fl80 in cash and awaits a large tip. [Aside: this is why the forms and envelopes do not carry any trace of these charges being paid.]

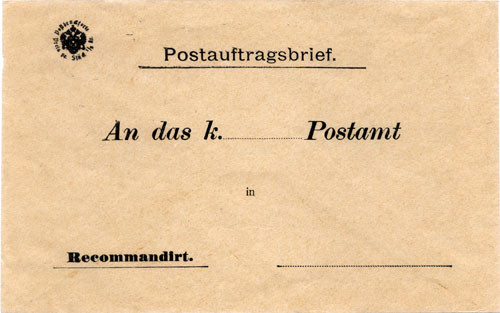

In late May 1883 [PVOBlatt 60 of 23 May], official envelopes were introduced at a price of ˝kr, but people could still use their own if they preferred. At the same date, a light green envelope was introduced, for sending back the Anlage if Alice did not pay the sum demanded

In late May 1883 [PVOBlatt 60 of 23 May], official envelopes were introduced at a price of ˝kr, but people could still use their own if they preferred. At the same date, a light green envelope was introduced, for sending back the Anlage if Alice did not pay the sum demanded

From 1 July [PVOBlatt 70 of 28 June] the sender was allowed to include a completed Postanweisung form in his envelope, instead of relying on the delivery office’s best efforts. He had to write "Auftrags-" before the title "Postanweisung". He was also permitted to add reference numbers, and could prepay the fee if he wished.

On 1 Nov [PVOBlatt 100 of 16 Oct] the Postauftrag service was extended to Bosnia, Hercegovina and the Sanjak. For details see Austria 154 page 18.

On 14 Dec [PVOBlatt 117 of 14 Dec] the forwarding of Postauftrage to a new delivery address was banned.

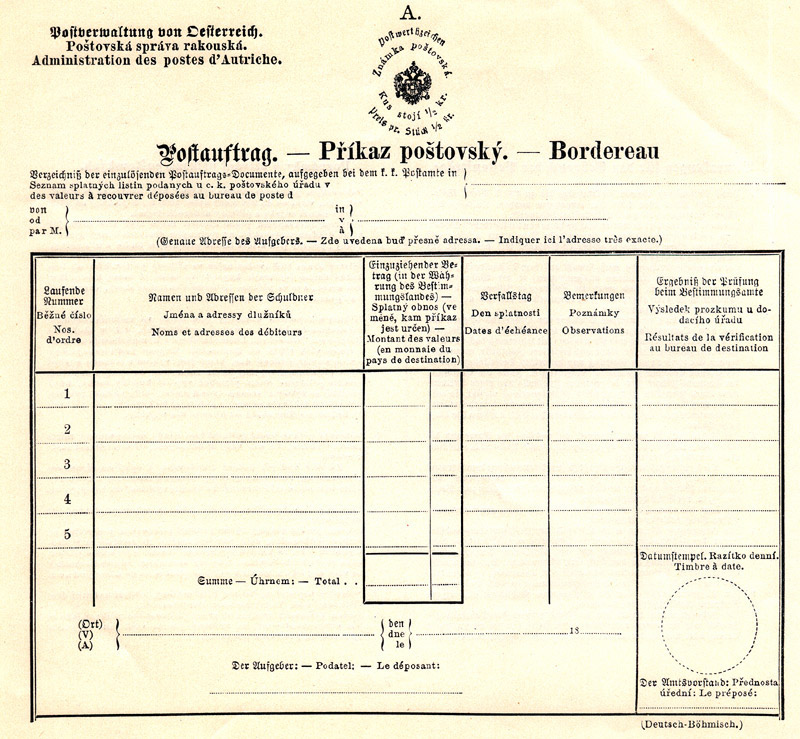

From 1 May 1886 [PVOBlatt 42 of 17 April] the service was extended to foreign countries such as Germany, Belgium, France, Italy, Luxembourg, Romania, Switzerland; and a long list of specified Post Offices in Egypt. A range of official forms was created, catering for sending, successful delivery, failure to deliver, and so forth. The form below is the German-Czech version of the one for the claimant (Bob above) to list the recipients (Alice, Eugenie, Iolanthe, Ophelia, Urania etc); it was permitted to put several payment-demands on the one form provided they were all handled by the same office. These multi-language forms were introduced in February 1887 by PVOB 17 of 16 Feb.

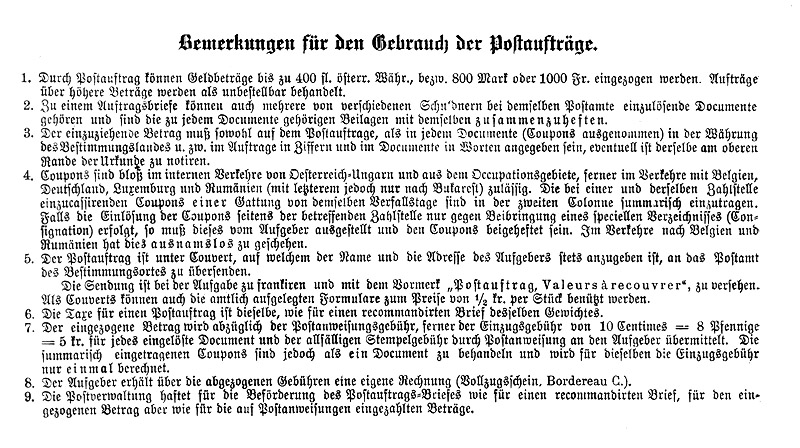

The regulations were many and detailed! Since this is an international postal document, it also has the headings in French. The instructions on the back are for Austrian postal staff so are only in German!

From 1 April 1903 a "notification service" was introduced, analogous to the "undeliverable packet" form. The sender completed a special form asking to be informed if the item was not accepted and paid for on first presentation to the addressee, or a Frist (period of grace) was asked for, or one of the documents was refused. A fee of 25h was charged. All the details would then be written on a Benachtrichtigungschreiben which was sent back to the sender; he could choose what to do next, including "send it back to me" and "redirect it to the Post Office at XX".

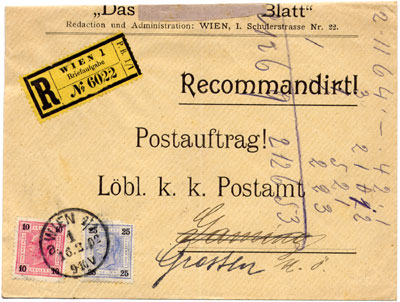

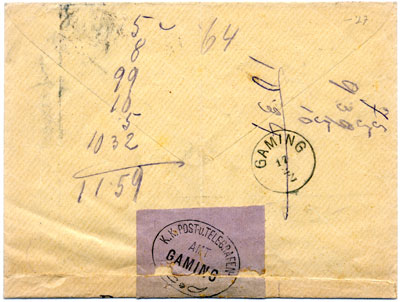

Sent in 1902 by a publisher in Vienna; franked with adhesives: 10kr post & 25kr registration. Redirected by the Gaming post office (whose stamp is on the resealing label) to Gossen – "contrary to 1902’s Regulations"!.

From 15 September 1906, claims and payments of over 1000Kr were permitted but subjected to a typically complex set of regulations.

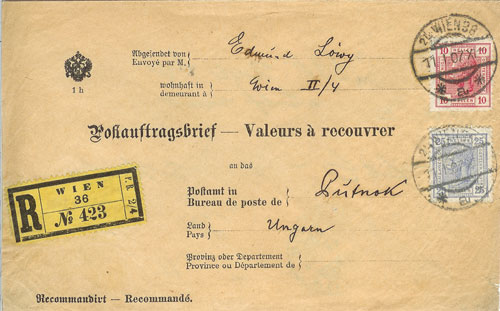

Envelope sent in 1907 from Vienna to Hungary. It’s the sold-at-the-Post-Office envelope introduced by the 1886 extension of service to foreign countries (it’s PVOBlatt 42 appendix B). It seems to have replaced the German-only version in inland service since all known specimens of the time are dual-language.

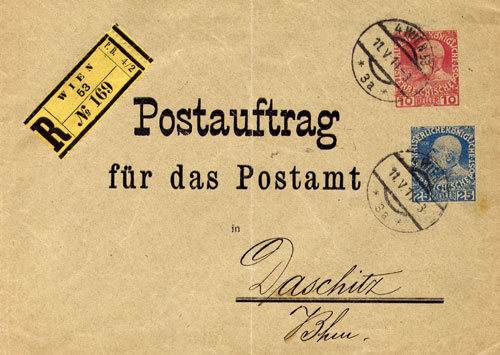

Envelope with privately imprinted 10kr & 25kr to pay registration and postage.

Sent on 11.5.1911 from Vienna to Daschitz

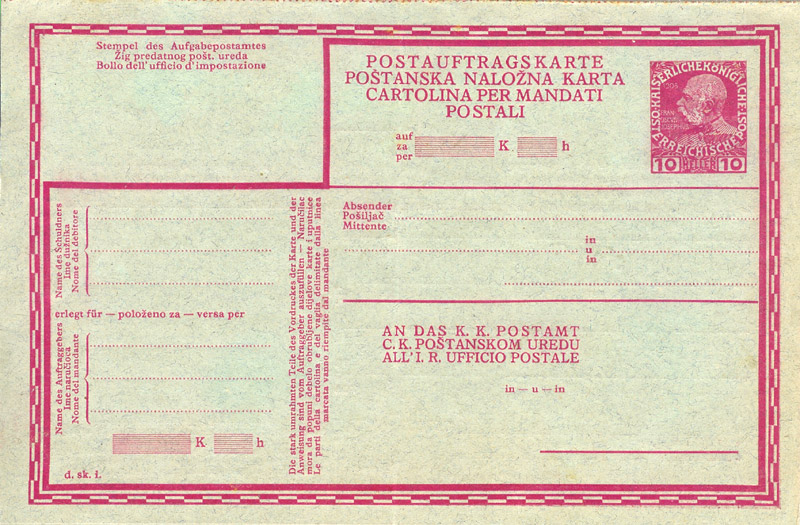

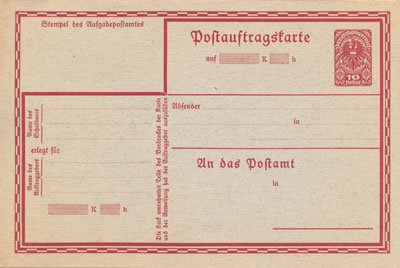

From 1 July 1913 a new stand-alone Postauftragskarte appeared; it was for claiming small amounts up to 10Kr (typically magazine subscriptions and the like). An inclusive charge of 10h was made, shown by a 10h imprint. An Auftragspostanweisung formed a second part, which the sender also filled in. This is the three-language German-SerboCroat-Italian version. From 1 November these cards could be sent to and from Bosnia-Hercegovina and the Sandjak.

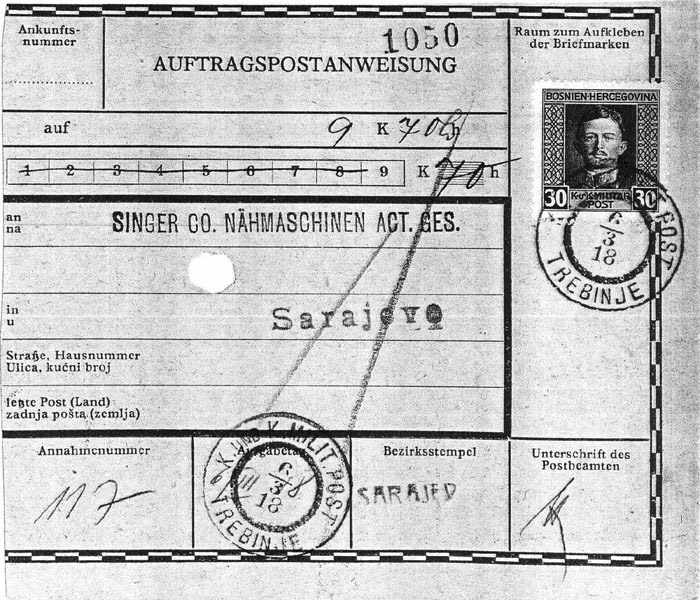

Money order, originally attached to a Postauftrag, sent from Trebinje on 6 Mar 1918, to Sarajevo. 20h fee + 10h for collection.

This Postordnung revoked all previous Postordnungs and their amendments and stated in 82 pages the detailed rules and regulations for every aspect of the inland postal service. It is the starting point for all inland postal matters until 1938 and to some extent after 1945. Sections 90-93 deal with Postauftragsbriefe; 94 with Postauftragskarte; and 118 with the charges.

90: A wide variety of documents (invoices, receipts, bills of exchange etc) may be sent in a Postauftragsbriefe, which the addressee can take possession of in exchange for payment of a stated amount not exceeding 1000Kr. [These documents, previously called ‘Anlage’, are now called ‘Forderungsurkunde’.]

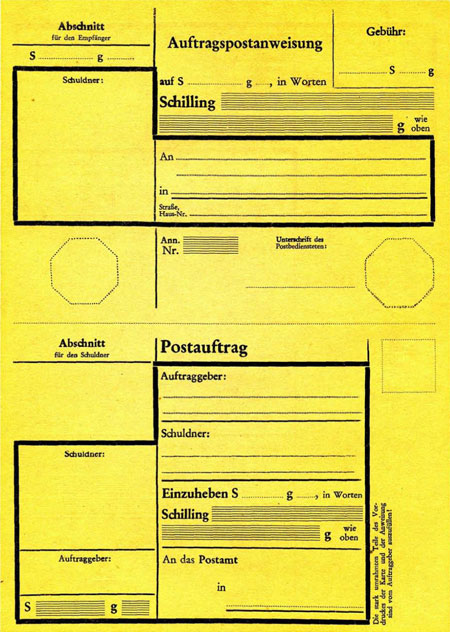

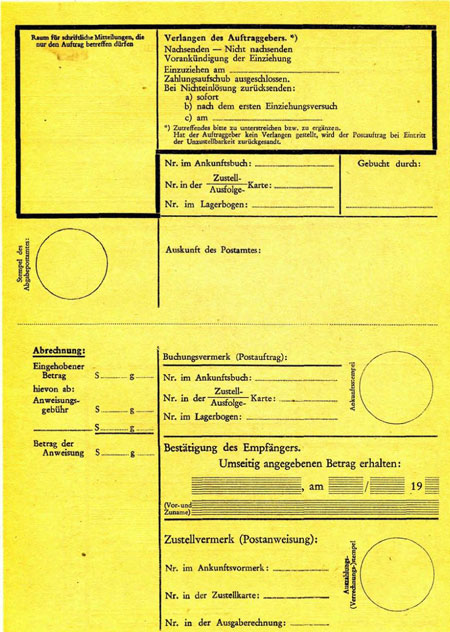

91: The Postauftrag details are to be entered on a 2-part form (sold by the Post Office at 3h) which has the Auftrag with the delivery instructions at the bottom; at the top is the Anweisung for remitting the payment back to the sender.

92: The sender is to put the form and the documents in an envelope, address it to the recipient’s Post Office, and add his own name and address. He can use a Post Office-supplied envelope, or supply his own which must be conspicuously marked Postauftrag.

93: Postauftragsbriefe are treated as registered letters, but any specified delivery date must be at least seven days after posting.

94: Postauftragskarte can be used to claim up to 20Kr; accompanying documents are impossible; they have an imprinted 10h stamp to cover the postage and are sold by the Post Office at 10h; privately-produced cards are forbidden. They are a 2-part card [similar to the Postauftrag of para 91].

118: If the recipient pays the amount claimed, the remittance back to the sender is charged as an ordinary Postanweisung and the fees deducted from the gross amount. If the recipient does not pay, the documents are returned to the sender who pays the Vorzeigegebühr.

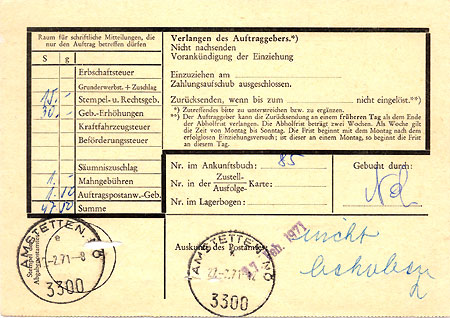

The "Vorzeigegebühr" was introduced in §168 of the 1916 Postordnung. It was a fee charged for the return to the sender of a C.O.D. packet, a Postauftrag, etc which had not been delivered to the addressee for whatever reason – normally a straightforward refusal to pay! It started at a rate of 10 heller, rising as inflation bit to 800Kr/8gr at 1st Oct 1925 and to 15gr by the Anschluss. It applied to inland post, and to foreign post till Aug 1921 and again from Dec 1924. Initially it was payable by postage adhesives. From 14 Jan 1920 postage dues were applied, redeemed in cash by the recipient ie the original sender. After the Anschluss, as the Reichspost didn’t use postage dues a simple cash payment was charged. On 1 Jan 1947, following the principle "let it be as it used to be", the Vorzeigegebühr reappeared as 15gr [BGBl 206 of 21 Nov 1946], soon rising to 30gr, and charged by postage dues. In 1955 it rose to 70gr – but in the 1957 Postordnung [BGBl 110] it was unceremoniously abolished.

The maximum permitted amount, and the postal charges, steadily rose as inflation bit. The Postauftragsbriefe continued to be treated as a registered letter of the same weight and destination.

The maximum permitted amount, and the postal charges, steadily rose as inflation bit. The Postauftragsbriefe continued to be treated as a registered letter of the same weight and destination.

On 15 Jan 1920 the Postauftragskarte limit was raised to 50Kr; further increases followed to 500,000K; for Postauftragbriefe it rose to 3 million Kronen! The illustration shows a 1920 issue Postauftragskarte

On 15 July 1922 the requirement was restated that a specified delivery date should be at least 7 days after posting. Also, Postauftragbriefe found un- or under-franked in letter boxes would not be delivered, but returned to the sender.

On 4 Oct 1923 the imprint on existing Postauftragskarte was devalued; old ones were to be used up as if they had no imprint and new printings didn’t have one. The cards were sold at a nominal fee of 200K.

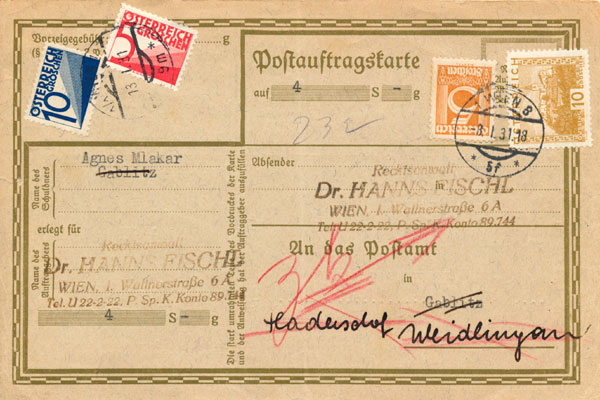

Imprintless card used in 1931 with 15 groschen postage for sending it from Vienna to Agnes Mlakar in Gablitz.

She didn’t pay the 4 Schilling demanded so Dr Fischl had to pay another 15 groschen Vorzeigegebühr to get it back.

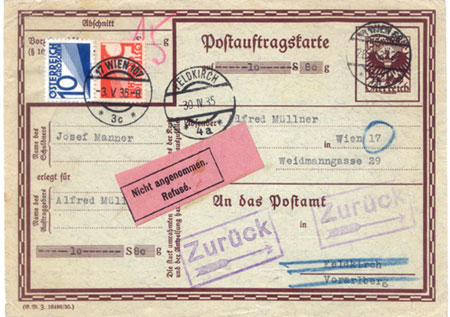

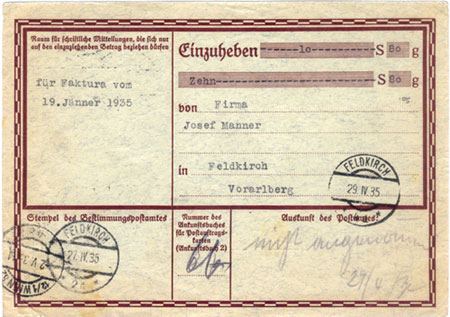

This Postauftragskarte is a request by Alfred Müllner in Vienna to J. Manner & Co in Feldkirch to pay 10Sch 80gr for an invoice dated 19 Jan 1935. This would be transacted at the Feldkirch post office. However Herr Manner refused; and Herr Müllner had to pay 15gr Vorzeigegebühr to have his card returned.

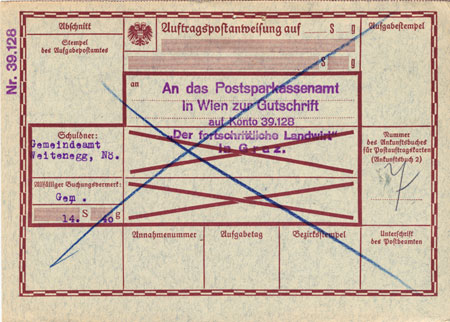

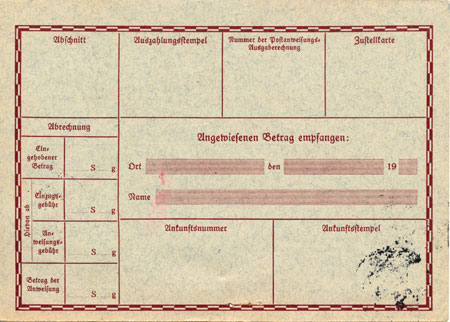

This is an Auftragspostanweisung, prepared so that the municipal authorities of Weidenegg could pay 14Sch40 into a Postsparkassen account to benefit "The Progressive Farmer" (probably a newspaper) in Graz. It’s unfranked and crossed out in blue so can’t have been used – although it could have been sent to Weidenegg in an envelope with a covering letter or invoice. Sometimes the rejected Postauftragskarte- Auftragspostanweisung pair were returned by the Post Office glued together; this shows the system to advantage but is difficult or impossible to make into an illustration!

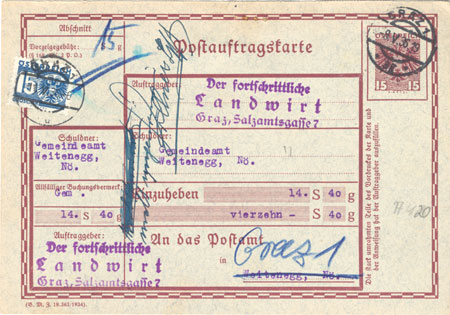

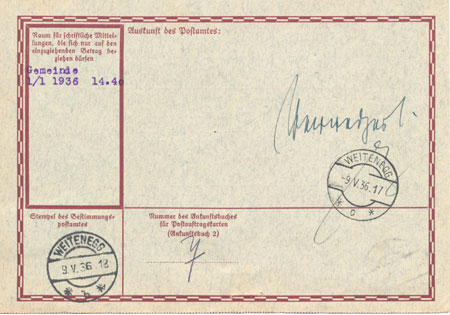

A Postauftragskarte showing the Dollfus Standestaat double-headed eagle imprint. Posted by The Progressive Farmer in Graz, again to the municipal authorities of Weidenegg in 1936, unpaid, sent back, and the 15 groschen Vorzeigegebühr duly levied.

The system was converted to the German one, which achieved similar ends using slightly different details. A Zahlkarte is sometimes encountered, especially in the Russian Zone until Dec 1945; It is an alternative remittance method alongside the Postanweisung.

By 1 Jan 1947 the Austrian system was fully back in action.

On 1 Sept 1947 it was clarified that the recipient must pay in full before receiving the documents, unless the sender had stated that a part payment was acceptable; and that the return remittance could be on either the official or a sender-supplied form. The charge was as previously, ie the same as that for a standard Postanweisung.

On 27 May 1957, Postauftragsbriefe and Postauftragskarte were combined and a unified card issued. Customers could choose between sending it as a card and as a registered letter (to which they could add enclosures), and had to frank accordingly. The actual card is in livid Post Office Yellow.

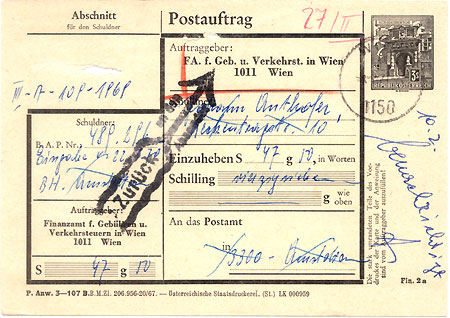

This Postauftrag is a request dated Feb 1971 from the Finanzamt für Gebühren und Verkehrsteuren in Vienna (they dealt with requests to postpone the payment of taxes) to someone in Amstetten to pay 47Sch 10gro. They didn’t, so the card was returned.

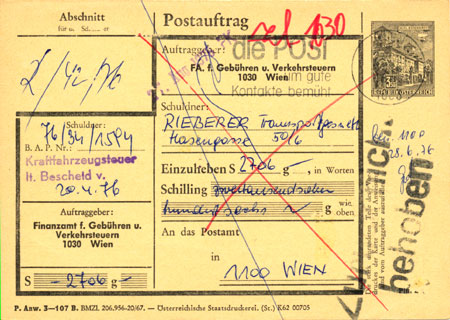

In the last week of February 1981, complex transitional arrangements were in force: this was to avoid difficulties when the system changed: from 1 March, the sender had to prepay (with postage stamps) the fees for remitting back the money, from which no deductions were made. The remittance would come to a Post Office account that the sender had specified; cash delivery was still available but at an extra fee. This may not have applied if the sender was a governmental organisation; this undelivered Postauftrag from the Finanzamt für Gebühren und Verkehrsteuren dated July 1997 was returned without any visible prepayment.

In the last week of February 1981, complex transitional arrangements were in force: this was to avoid difficulties when the system changed: from 1 March, the sender had to prepay (with postage stamps) the fees for remitting back the money, from which no deductions were made. The remittance would come to a Post Office account that the sender had specified; cash delivery was still available but at an extra fee. This may not have applied if the sender was a governmental organisation; this undelivered Postauftrag from the Finanzamt für Gebühren und Verkehrsteuren dated July 1997 was returned without any visible prepayment.

On 1 September 2003, the organisation of this aspect of Post Office services changed, and since then has changed again – so, this is a good date to end the article at. Also, from that date the option of cash delivery ceased.

Kainbacher, "Handbuch der Brief- und Fahrpost in Österreich-Ungarn 1588-1918", volume 2, pp 185-218

Kainbacher, "Postgebühren von Österreich 1919-2006 für den Inlandsverkehr", volume 3 part I pp 404-429

Reich- or Bundes-gesetzblatt (available on line) and Post (und Telegraph) Verordnungsblatt (accessible in Vienna)

You may have noticed that all the examples are either mint; or not-sent; or sent but returned and charged for with postage dues. Why aren’t there normally-used examples, liberated from the archives of offices or sold by the grandchildren of the recipients? There are at least three reasons for this anomaly.

1. An Austrian legal textbook published in 1926 has an interesting section 20 entitled "Eigentum an Postganzsachen und Postvordrucken" [Ownership of postal stationery and postal forms]. Paragraph 1 says "Postbegleitadressen, Postanweisungen und Postauftragskarten samt den darauf befindlichen Marken gehen mit der Aufgabe in das Eigentum der Post über. Translation: The three named forms together with any adhesive stamps that are on them become the property of the Post at mailing. Paragraph 2 says in colloquial translation: When you receive a package or the amount of a Postanweisung or a Zahlungsanweisung, you are only entitled to keep the coupon (Abschnitt) of a package card or of a Postanweisung. With a Postzahlungsanweisung you are entitled to keep the Buchauszug (the extract from the book or ledger), and with Postauftragskarten the coupon. It goes on: The Post has the right NOT TO DELIVER packages and money, and to treat what has been sent as undeliverable, if the recipient removes stamps from the package card or the Postanweisung and refuses to return them or to pay their face value.

2. As I understand the system, the Postanweisung generated by a Postauftrag is handled the same way as one handed over the counter. It's an instruction to the money side of the Post Office (the Postsparkasse) to remit money to somebody. All such went via Otto Wagner's Postsparkasse building in Vienna, even if from Innsbruck to Igls. The form brought to the recipient’s door (that he couldn't have) was not the same form as the originator had filled in. Indeed, with later versions of the system whereby payments could be made from or to a named P.O. account, Vienna would certainly have kept the original as authorisation for shifting the money.

3. When Post Office forms reached the end of the appropriate retention time, they were auctioned on the philatelic market as kilogram bags of "Skart" which consisted only of stuff they knew they could sell, ie items with adhesives. The rest was recycled as waste paper.

| Back to Austrian Stamps homepage |

©APS. Last updated 24 March 2011